If you have read through the entire series up to here, welcome! If you have not, please consider reading the whole series:

- Part 1: Encryption Everywhere

- Part 2: A Primer On Public-Key Cryptography

- Part 3: Certificates

- Part 4: Certificate Authorities & Chains Of Trust

- Part 5: Bootstrapping Trust

This article makes implicit heavy use of part 2 and part 3 of this series.

Root & Intermediate Certificate Authorities (CAs)

Not all certificates are the same! Certificates have different capabilities depending on their usage attributes and extensions. The previous article in this series mentioned a few of those attributes and extensions. Two of those were clientAuth, for client certificates, and serverAuth, for server certificates, which play an essential role in how a certificate is used during network authentication negotiations. These roles are crucial, as they are a contract for what attributes and extensions should be included in the certificate to make it useful. For example, a server certificate usually finds it useful to include Subject Alternate Names (SANs). A SAN can be used to tie a certificate to a specific domain name (like ziti.dev). However, a client certificate will not have use for those same fields.

The roles of certificates and the attributes/extensions they have are not always strictly followed. Some systems, such as web browsers, require SANs on a server certificate. That wasn't always the case. Before that, the Common Name field in the subject information contained the domain name. Some systems still rely on that convention.

Another type of certificate is a Certificate Authority (CA) certificate. A CA is a key pair with a certificate that has a unique purpose: to sign other certificates. CA certificates have a special CA flag set to "true." This flag alone does not grant the CA certificate any power, but if a system trusts that CA, it then allows that system to trust any certificate that CA has signed. As mentioned in previous parts of this series, trusting a CA is a software or operating system configuration process. This process can be done in multiple ways depending on the system: adding it to a store, a specific folder, or adding lines to a configuration file.

Your operating system, right now, has its own set of trusted CAs. Most operating systems come with a default list installed and maintained by your OS developer. Over time this list is added to and removed from as trust is granted or withdrawn. Some pieces of software come with a list of CAs that are used instead of or in addition to the OS's CAs. The power of a CA comes not by its creation but by it being trusted.

CAs come in two flavors: Root CAs and Intermediate CAs. Root CAs are the egg or the chicken (depending on your viewpoint) of the CA trust chicken-and-egg problem. Trust for CAs has to start somewhere. With CAs, it is the Root CA. A Root CA can sign certificates that are themselves CAs as well. Those certificates represent Intermediate CAs. Layers of CAs starting with a root and adding intermediates along the way allows the private key for the Root CAs to be kept in a highly secure environment, which is not convenient to use for signing. This security means that the Root CA has a far less likely chance of having its private key compromised. Intermediate CAs are put into less secure environments and, if compromised, can be revoked. Trust is usually put into the Root CA, and since it was not compromised can remain trusted. Compromised intermediate CAs can be blacklisted.

Running a public CA is serious business if you wish to be publicly trusted. The organizations running a CA have to have strict protocols that verify the security and safe handling of the CAs private keys. If the private key is compromised, it can be used to sign other certificates for malicious intents. Any system that trusted the compromised CA will now trust any maliciously signed certificates. This will compromise all certificates signed by that CA.

Public CAs are maintained by organizations such as DigiCert, Let's Encrypt, and others. Anyone can create private CAs. The only difference is that the number of systems that trust a private CA is much smaller than that of a public one. CAs are a cornerstone of bootstrapping trust. Trusting the proper CAs can grant trust to a large number of systems.

Chains of Trust & PKIs

Part three of this series introduced that certificates self-sign or sign another certificate. Certificates are usually signed via Certificate Signing Requests (CSRs). A certificate signing itself is called a "self-signed certificate" and is an indicator of it being a root CA if the CA flag is also set to true. A root CA can sign other certificates that also have the CA flag set to true. Those types of certificates are intermediate CAs. Any CA, root or intermediate, that fulfills a CSR and signs the enclosed certificate will generate a non-CA certificate as long as the CA flag is false. These certificates are "leaf certificates."

The term Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) is used to describe all of the outputs that are generated when a CA is created. That includes the root, intermediates, and leaf certificates. It also optionally includes all of the systems, processes, procedures, and data used to manage them. For the purpose of this article, and simplicity, let us stick to the certificates only.

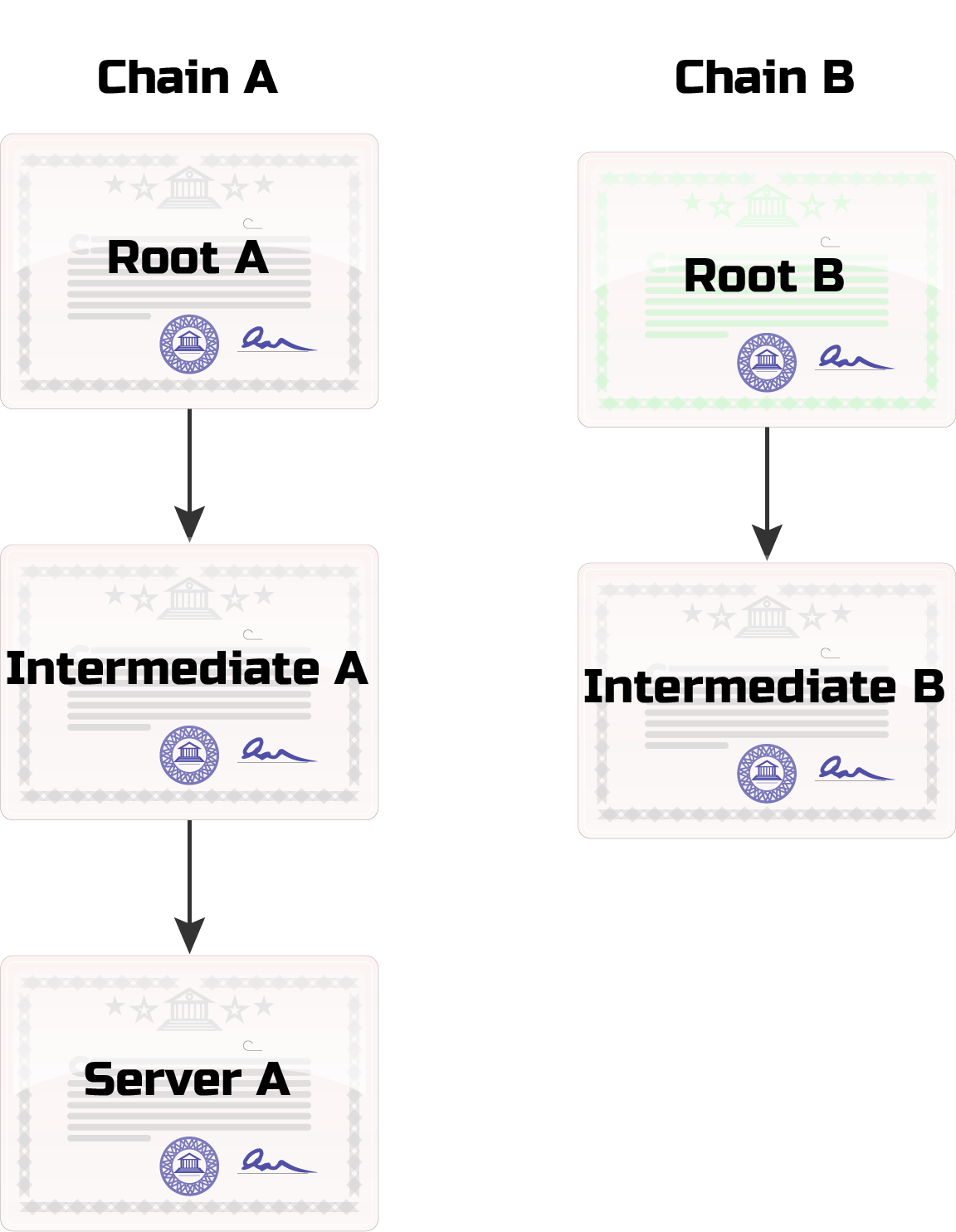

Consider the following PKI setup:

- Two root CAs:

- Root A

- Root B

- The root CAs each sign an intermediate CA via CSR:

- Intermediate A

- Intermediate B

- A server wishes to have a certificate to have Root A's trust extended to it.

- A key pair is generated

- A CSR is created and submitted to Intermediate A to sign

- The CSR is fulfilled.

- Server Cert A is created and signed by Intermediate A

Visually this would appear as follows:

This PKI has two chains of trust: Chain A and Chain B. They are called chains because the signatures link the certificates together. Root A has signed Intermediate A's certificate and Intermediate A has signed Server A's certificate. Programmatically we can traverse these signatures and verify them using the public certificates of each signatory. Trusting Root A will trust Server A.

The second chain, Chain B, does not sign any of the certificates on Chain A. As expected, Trusting either of the CAs from Chain B does not grant any trust to the certificates on Chain A. Chain B highlights the fact that any system may have multiple chains of trust that do not interact in any fashion.

Returning to Chain A, trusting Intermediate A designates it as a "trust anchor." Any certificate can be a trust anchor. The certificate used as a trust anchor determines which certificates will additionally be trusted. A leaf certificate as a trust anchor only trusts that one certificate. Trusting a CA trusts all certificates that it has signed itself or any of its intermediates. In the diagram above, trust only flow downward.

- Trusting Server Cert A will only trust that one server certificate

- Trusting Intermediate A will trust Server Cert A and any other certificate it signs

- Trust Root A will trust Intermediate A and Server Cert A and any other certificate Root A signs (intermediate CA or not) and in turn, any of the certificates they sign

Trusting a CA that has signed many certificates allows public certificate trust to scale. This is how trust scales for web traffic. Companies like DigiCert, IdenTrust, GoDaddy, etc. have their root CA or one of their large intermediate CAs trusted. Those CAs sign certificates for websites. All of our devices trust those website certificates because the CA has signed them.

Distributed Systems & CAs

The goal for any private distributed system should be to have certificates verified on both sides: clients verify servers and vice versa. This behavior is a tenant of Zero Trust - do not trust, verify. Verification should be done on every connection before any data exchange. Over TLS, which secures HTTPS, this would be "mutual TLS" or "mTLS." Most public websites do not require mTLS. Instead, they use TLS with the client validating the server. For public web traffic, the server wishes to be trusted widely. The reverse is not necessary. If it is, websites use an additional form of authentications, like usernames and passwords, to verify the client's identity. Public key cryptography is a stronger authentication mechanism, but it is also difficult for the general public to set up, manage, and maintain.

The same is true for distributed systems. Most don't secure anything at all or only verify servers. It is inherently insecure and can cause issues depending on the setup of the system. Ziti is a distributed system that abstracts away this security setup for both its internal routers and client SDKs. This setup allows application-specific networking with strong identity verification, powerful policy management, flexible mesh routing, and more. The goal of this series is to focus on bootstrapping trust. So in the last article we will come full circle and see how all of this relates to bootstrapping trust for Zero Trust networks.